Some 400 kilometers from the nearest sea, engineering students at Switzerland’s ETH Zurich are hard at work on cutting-edge robots that may change the way the world’s oceans are studied.

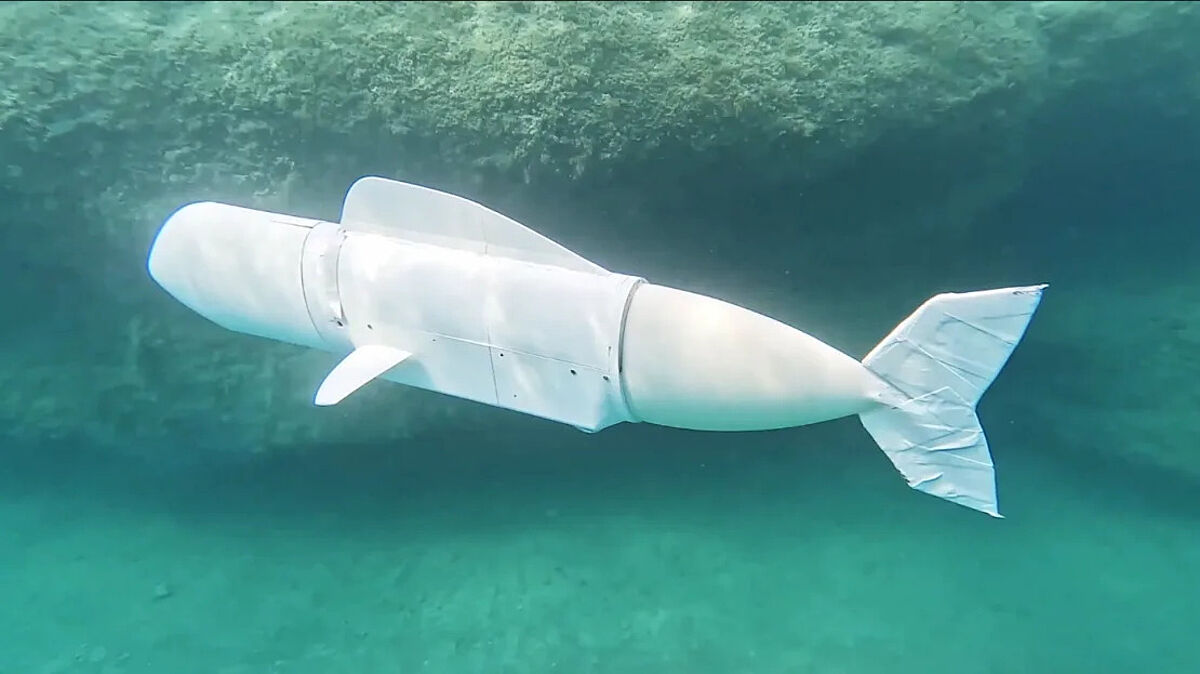

“Eve” the robotic fish swings its silicone tail side to side, powered by pumps hidden inside, as it glides fluidly through Lake Zurich’s chilly water, where it is being tested by SURF-eDNA. The student-led group has spent the past two years building a school of soft robotic fish – of which Eve is the latest.

“By making Eve look like a fish, we are able to be minimally invasive into the ecosystem that we’re surveying,” says master’s student Dennis Baumann, adding that the biomimetic design should prevent other fish or sea life from being startled by her presence. “We can mix, we can mingle in the ecosystem,” he adds.

Eve’s ability to camouflage itself as a fish isn’t its only utility. The autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) is also equipped with a camera to film underwater, and sonar, which when paired with an algorithm, allows it to avoid obstacles.

The AUV also features a filter to collect DNA from the environment, known as “eDNA,” as it swims. The eDNA particles can be sent to a laboratory for sequencing to determine what species live in the body of water.

“All of the animals that are in the environment, they shed their DNA, so there’s DNA floating around that we can find,” says Martina Lüthi, a postdoctoral researcher at ETH Zurich.

The students hope that Eve will be able to give scientists a more detailed picture of the oceans and their inhabitants. Despite covering more than 70% of our planet, much of what lies below the surface remains a mystery.

Tools like AUVs and remotely operated vehicles are increasingly being used to explore the ocean and learn more about underwater habitats. California-founded startup Aquaai, for example, has developed drones resembling clownfish, that can collect information like oxygen, salinity and pH levels in waterways; and last year, a rover captured the deepest-ever filmed fish at a depth of 8,300 meters.

The use of eDNA to monitor biodiversity is growing, but sampling can be rudimentary – some scientists still collect it by scooping water into a cup leaning over the side of a boat.

More advanced tools that can study environments in more detail could be vital for better protecting Earth’s oceans, at a time when ocean habitats are facing unprecedented threats from climate change, overfishing and other human activity.

“We want to build a reliable tool for biologists,” said Baumann, who added that he hopes one day they can scale up their technology, so it is accessible to any scientist who wants to use it. “Maybe we can prevent species from being endangered or dying out.”