Not all viruses infect people, some, called bacteriophages, infect bacteria. Bacteriophages, also known as phages, are more complex than many viruses that we're familiar with and carry large genes that can be used to attack the bacteria they infect. Researchers have now found giant phages in samples from almost thirty different environments, including a Tibetan hot spring, oceans, hospital rooms, and pregnant women. The work, reported in Nature, revealed 351 massive phages, which all carry genomes that are four or more times bigger than the genomes of typical viruses that have been identified. This includes the largest bacteriophage ever found, which has a genome of 735,000 base pairs, roughly fifteen times bigger than average phages.

"We are exploring Earth's microbiomes, and sometimes unexpected things turn up. These viruses of bacteria are a part of biology, of replicating entities, that we know very little about," said the senior study author Jill Banfield, a UC Berkeley professor of earth and planetary science and of environmental science, policy, and management. "These huge phages bridge the gap between non-living bacteriophages, on the one hand, and bacteria and archaea. There definitely seem to be successful strategies of existence that are hybrids between what we think of as traditional viruses and traditional living organisms."

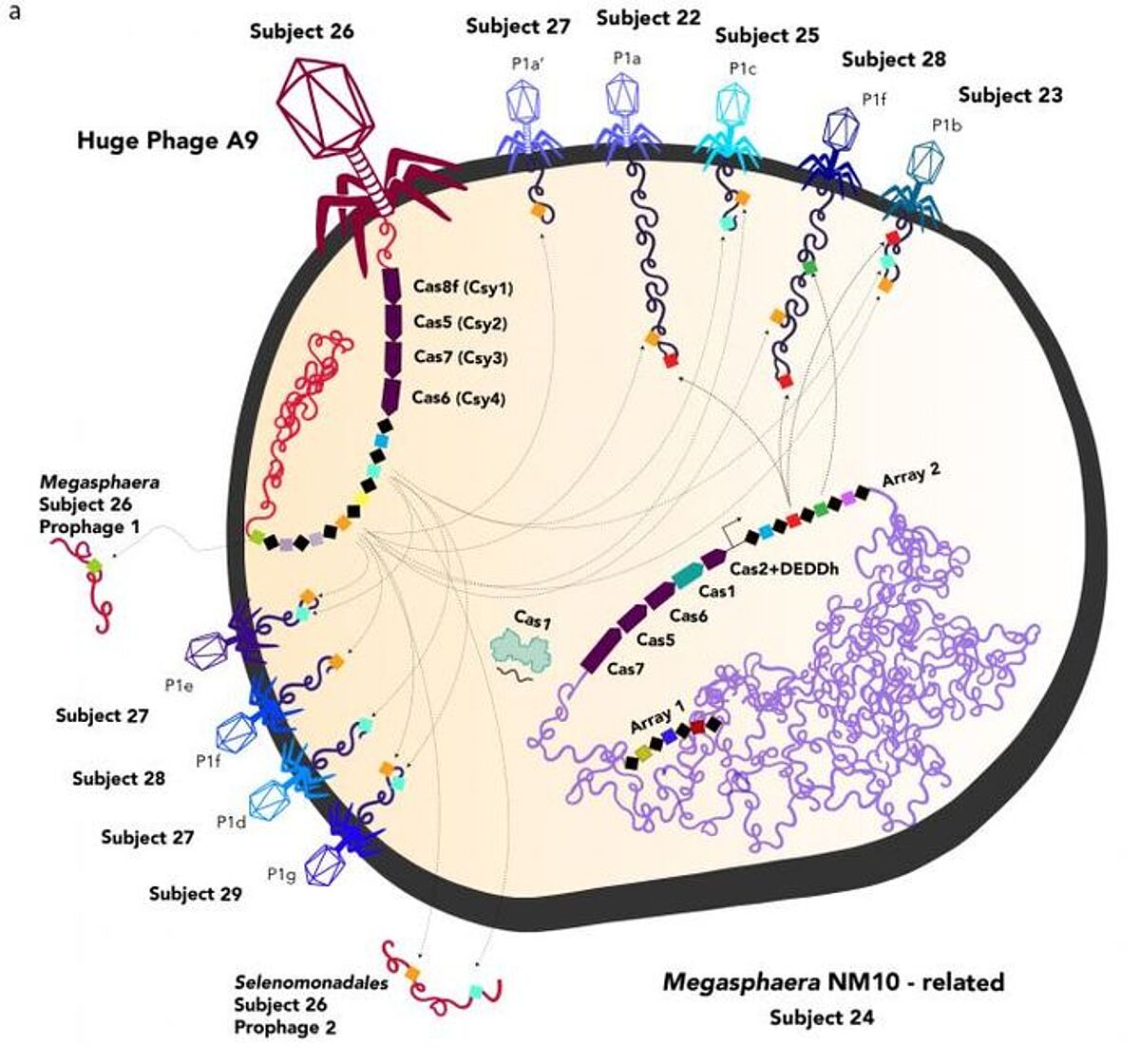

The CRISPR gene-editing system comes from a bacterial defense mechanism against phages, and some of that CRISPR system can be found in large phage genomes. The phages may infect bacteria, and a viral CRISPR can alter the bacterial CRISPR, potentially to target other viruses. One phage is even able to generate a Cas9 protein that is similar to what's used in the CRISPR editing system. The team called this protein CasØ.

"It is fascinating how these phages have repurposed this system we thought of as bacterial or archaeal to use for their own benefit against their competition, to fuel warfare between these viruses," said UC Berkeley graduate student and study co-first author Basem Al-Shayeb.

"In these huge phages, there is a lot of potential for finding new tools for genome engineering," said study co-first author, research associate Rohan Sachdeva. "A lot of the genes we found are unknown, they don't have a putative function and may be a source of new proteins for industrial, medical or agricultural applications."

Viruses are able to move genes between cells, and live in the human gut microbiome with bacteria and archaea, so this work may have implications for human disease.

"Some diseases are caused indirectly by phages, because phages move around genes involved in pathogenesis and antibiotic resistance," said Banfield. "And the larger the genome, the larger the capacity you have to move around those sorts of genes, and the higher the probability that you will be able to deliver undesirable genes to bacteria in human microbiomes."

Most of the genes carried in the bacteriophage genomes encode unknown proteins, but the scientists found genes that are crucial for generating cellular machinery called the ribosome, which makes proteins (in eukaryotic cells this machinery is an organelle but it's also found as a complex in prokaryotes). They also identified genes that move amino acids to this machinery when proteins are being translated.

"Typically, what separates life from non-life is to have ribosomes and the ability to do translation; that is one of the major defining features that separate viruses and bacteria, non-life and life," Sachdeva said. "Some large phages have a lot of this translational machinery, so they are blurring the line a bit."

"The high-level conclusion is that phages with large genomes are quite prominent across Earth's ecosystems, they are not a peculiarity of one ecosystem," Banfield said. "And phages which have large genomes are related, which means that these are established lineages with a long history of large genome size. Having large genomes is one successful strategy for existence, and a strategy we know very little about."